iPhone location data doesn't include a full movement profile

The hype around Apple's iPhone tracking loses some of its urgency when users take a closer look at the database, which doesn't contain a full profile of the user's movements and only stores each location once – and it may also contain places that the user didn't actually visit. It is, therefore, impossible to establish a user's movements with any certainty. However, what remains an explosive issue is that the creation of the file can't be prevented, and that the file ends up on a user's PC in unencrypted form without any further user input.

The hype around Apple's iPhone tracking loses some of its urgency when users take a closer look at the database, which doesn't contain a full profile of the user's movements and only stores each location once – and it may also contain places that the user didn't actually visit. It is, therefore, impossible to establish a user's movements with any certainty. However, what remains an explosive issue is that the creation of the file can't be prevented, and that the file ends up on a user's PC in unencrypted form without any further user input.

The database essentially contains two tables, one that lists Wi-Fi routers and another that lists mobile radio transmitters which are each linked to a set of coordinates and a timestamp. Wi-Fi networks are identified via their MAC address, while mobile network cells use four codes (MCC, MNC, LAC and CI), for example MCC=235 for the UK and MNC=02 for O2, MNC=15 for Vodafone and MNC=20 for Three; the LAC/CI codes are allocated by the mobile telephony providers themselves.

Only one record of every Wi-Fi access point and mobile network cell exists in the database. Records are periodically refreshed to receive the latest update's timestamp. Consequently, the timestamp only indicates the most recent time at which the iPhone updated a database record. The database does not indicate whether a user was within range of this mobile phone cell or Wi-Fi network before, nor does it specify whether the user revisited it later.

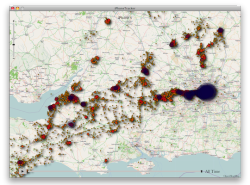

![]() Visualising the iPhone's geodata cache.

Visualising the iPhone's geodata cache.

Source: iPhoneTracker

Furthermore, the user may not even have been close to the listed locations; tests by c't magazine, The H's associated publication in Germany, yielded interesting rogue results, particularly in terms of the Wi-Fi locations: for example, an iPhone was allegedly in Hanover, Düsseldorf, Barcelona, Darmstadt and New Delhi all at the same time; on closer inspection, it supposedly was at exhibition grounds in Hanover, Düsseldorf and Barcelona, close to a Motorola subsidiary in India, and at a university in Darmstadt. The solution to the mystery: on that particular day, the iPhone user walked across the CeBIT show ground in Hannover, and the iPhone probably came within range of several Wi-Fi routers that were still listed with incorrect GPS data in Apple's database. (The maintenance of this database is the very reason why Apple, like Google with Android and Microsoft with Windows Phone 7, has collected anonymised location data for quite some time.)

Although the mobile network locations listed in our iPhone database matched the actual locations with greater accuracy, rogue results that may have been caused by bad cell signals could also be found in this table. The table may also have been obsolete, because mobile telephony providers do occasionally relocate their cells. Other explanations are conceivable, for instance peculiarities in the algorithm that determines the selection of surrounding mobile network cells, potentially from other LAs, that are passed on to the smartphone.

The timestamp also only provides limited evidence, as a huge number of entries are rewritten with each database update. For instance, an iPhone owned by a member of our editorial team received more than 430 updated Wi-Fi locations and over 120 updated mobile network cells (within a radius of a few hundred metres from the editorial offices) in one update – all with the same timestamp. In addition, not all Wi-Fi access points (APs) and mobile network cells are updated on a regular basis. For instance, various Wi-Fi APs within our internal corporate network hadn't been updated for months, while the small AP that was used when the iPhone was first activated was given an update only on Tuesday (26 April) afternoon.

Therefore, the timestamp doesn't denote the time a user first visited a location, because the database entry could have been updated. Neither does it denote when a user last visited the location, because not all cells and APs receive regular updates. It doesn't even conclusively prove that the user visited this location at all, as both Wi-Fi and mobile network entries can potentially originate from totally different places. Only one conclusion is possible: if several location entries over a longer period of time produce a halfway conclusive path, it is likely that the iPhone was carried along this path – perhaps not for the first, and perhaps not for the last, time.

In fact, enough old cell entries remain without updates to provide a good impression of a user's long-term movements. The rarer the visits to a certain place, the more detailed the record. Attackers have another option: they need to obtain regular access to the victim's computer and take the database file. Comparing the databases will allow various conclusions to be drawn, although it still won't provide a full movement profile.

Tests by c't magazine confirm the currently available information stating that it is impossible to disable the database updates. Even with the location service disabled in the preferences, the database was updated occasionally – although it appeared to happen far less frequently than when the location service was enabled. With the limitations mentioned above, such updates again allow a rough movement profile to be established.

There are at least two ways of erasing an iPhone that will remove the database, for instance before selling the phone: we managed to lose the file by deleting it via iTunes and entering the wrong passcode ten times (To enable: Settings / General / Passcode Lock / Erase Data). But beware: immediately after the iPhone is reactivated and an internet connection established, the device resumes its logging of GPS updates, and hundreds of Wi-Fi access points and mobile network cells in the vicinity will be stored within only a few minutes.

(crve)

![Kernel Log: Coming in 3.10 (Part 3) [--] Infrastructure](/imgs/43/1/0/4/2/6/7/2/comingin310_4_kicker-4977194bfb0de0d7.png)

![Kernel Log: Coming in 3.10 (Part 3) [--] Infrastructure](/imgs/43/1/0/4/2/3/2/3/comingin310_3_kicker-151cd7b9e9660f05.png)